She crouched as her sister chewed her neck, then off she flew. Returning with a load of caterpillar, she jammed her head into cell after cell, plunging in to feed the larvae. The smallest ones needed to stretch to reach the food, and she let them know when to do it by drumming her antennae on the inside of the cell. For me, that soft sound of drumming is the sound of summer. And figuring out what those wasps were doing and why they had evolved to do it occupied me for a quarter century. Why? How can I convey the wonders of field biology discovery? How can I explain a fascination so absorbing it took me out for 14 hour days into the heat of the Texas hill country? Well, one thing I can tell you is that there are thousands of us, and my hope for the planet rests largely with the next generations of field biologists.

Decades after I first set eyes on those wasps, we returned again. It was a hot April day as we walked down the path at Bracktract last week. The cedars seemed oppressive, perfuming the overheated air. Ghosts of past events were everywhere. We passed the Bush green house. We passed a sign for the mountain lion trail. That sighting was after I was no longer working there. The rare plants garden had various plants in it but I could not tell if they were rare. We headed for my best Austin talisman: the tractor shed at the bottom of the garden. It doesn’t look like much.It is open on the front, and entirely made of corrugated tin hammered to beams. But it was here that back in 1976 Dale Lewis dared me to put some dabs of paint on the wasps, Polistes exclamans, we later found out. We did so, enabling us to recognize individuals, and were treated to a regular soap opera of hierarchies, moves to new nests, aggression, egg laying, and care of the young. I was started on my research career, jettisoning all other plans.

If you saw that shed, and its wasps, it wouldn’t mean much to you. The same is true of the other projects out there, which makes the value of a field station so hard to communicate. It looks like little is going on, but this is totally untrue. In some fields the plants are growing, maybe tagged with markers. They don’t need to be watched all the time, and don’t even need the specialness of a field station. The best projects are on the natural organisms that only live and behave naturally in large, native habitats. The 82 acres of BFL are enough for insects and other smaller organisms.

The windows into the secret lives of animals, plants, and microbes are often elusive. You need a guide, the scientist who is studying them, and then it becomes obvious. When we go to the tropics, we look for those guides, a local bird expert, someone who loves fungi, or the wasp specialist. With such a guide, a natural place is transformed. Creatures and blooms that were hidden are revealed, and their stories told. In the tropics nearly everything seems rare, but the specialists find their organisms easily.

At Bracktract last Friday we had no such guide. I didn’t even know where many wasps were, but remembered thousands of nest surveys as I walked along the invisible map in my head leading me from nest to nest, often in the predawn when they were tamer. We saw the signs of research past like the small mammal walls that Frank Blair put in back in about 1966. And we saw the signs of research present in the form of hanging trays with rotting fruit covered with butterflies.

It wasn’t until I looked at the photographs when I got home that I saw that the butterflies feeding on the rotting bananas were numbered. We saw 335, 310, and 301. Someone is peeking into a corner of Bracktract life I never knew! I emailed the director, Larry Gilbert, and he told me the best story, one of collaboration, comparison, exploration. You see, the butterfly trays and traps were put out by a grad student for comparison with a rare butterfly in Florida. Larry encouraged him to complement his Florida study with a study of a similar butterfly in a safer place. Differences make it easier to see novelty. So that’s neat, a great reason for a study, but it gets even better. An undergraduate noticed that another butterfly species, a really common one, was also going to the traps and baits. If she studied this species, she could take advantage of the equipment already in place. The grad student agreed, and shared his equipment. Both their lives are enriched, and I hope they are transformed the way I was.

Here is exactly what Larry said: Robert McElderry, a PhD student at U of Miami is doing a population study of leaf wing butterflies (genus Anaea). His interest is in the endangered Florida leafwing. I’m on his committee and suggested that he do a parallel study on a more common member of the genus. He has >15 baited traps fermenting fruit) across BFL. Several other butterflies, including the very abundant hackberry butterflies genus Asterocampa sp. (brown with lots of eye spots) also get caught in his traps. One of the students in my field class (Emily Wieweck) is studying the hackberry butterfly population for her independent project. Robert kindly let her remove and number the individuals caught in his traps. Emily uses the roadside open bait stations that you saw as “recapture sites” where one can read numbers without actual capture.Emily is a geosciences major who seems to be enjoying this diversion into ecology.

Sometimes it takes a bait, or a nest box to make something rare into something common, at least at a certain place. We struggle to understand how organisms adapt to their environment. This understanding is important for many reasons writers more eloquent than me have articulated. What changes might occur with permanent warming are some. Places like Bracktract are crucial, and always seem threatened. We work hard to explain their importance, to get administrators to peek into the lives of the organisms, and their students. For now it has been successful here, but the fight to keep this research treasure will never be over.

It’s the wasps that bring me back. That and seeing my old, old friends John and Grace Crutchfield, resident managers. Wonder what I saw last Friday? Wonder what those nests meant to me? Here’s just a bit to explain those photos. These two nests have their queens, and they are slightly larger than the workers. The first workers are small because the colonies are under pressure to get the first workers out early so they can help care for the brood, those pink or white larvae in the cells. The thing about evolution is it is all about tradeoffs. Larger workers might be more effective foragers, but if a summer tanager knocks the nest down and eats the brood, there will be no foragers at all. Adult wasps can fly away from the bird, and live to build another nest. So genes that cause early, small worker production are favored.

The queens look fierce and invulnerable, but there is a clue that this is not the case, right on both these nests. It is the pale ones, with all yellow faces, and long, thin antennae. OK, maybe you can’t see that about the antennae, but males have 13 antennal segments, and females have 12. And they are shaped differently. In these two photos, the males also have black eyes, but that just means they emerged recently. One of the females, middle right in picture 2, also has black eyes.

How does a male tell us the queen might die? Well, normally wasp colonies make workers all spring and summer, building up their numbers so they can produce a huge brood of reproductive future queens and males in the fall. The logic is you make the factory, then the output. A worker at this time could mean four reproductives later on, while a male at this time helps not at all. After lurking around on the nest a few days, stealing food from the larvae and workers, the males fly off and look for mating opportunities at the flowers.

Oh dear, this is getting a little complicated. You see, all biology is a web. Pick up and try to explain one strand, and you will find the whole natural world is attached. Who would be at the flowers waiting for these males? Don’t the queens just mate once, in the autumn before hibernating? Well, yes. And aren’t those hard workers virgins, lacking developed ovaries? Why would a sleek caterpillar hunter burden herself with ovaries bulging with eggs? Wouldn’t that be inefficient? Well, yes, but if the queen dies, having a back-up plan would be good. In this species, workers have developed ovaries, and the older they are, the more developed they get. So if the queen dies, the oldest worker will fly off, find a male, mate, and take over reproduction in the colony. I was very excited when I first discovered these early males, because it was something different, a story waiting to be explained.

I also found something else. It answers another question, one related to hiding from those birds, and maybe also about conflict in the nests. It turns out that from really successful, large colonies, say with 10 workers, an old worker will begin a new nest in a more hidden place before there were any threats to the original nest. Sometimes the original queen will also start another nest in a more hidden place. At first workers and queens visit both nests, but gradually the workers settle on one nest or the other, and each has its own queen, either the original queen, or a worker who has mated. They would stay separate unless a predator hits one of the nests. In that case, the adults fly to the other nest and rear those babies. After all, it is all in the family, and they are all related to each other, so the genes for cooperation will be passed on. The advantage to having a spare nest, a head start, a kind of insurance, another basket for your eggs, is clear.

Not all species of wasps in this area have early males or satellite nests. The big red Polistes carolina that nest in dark hollows do not. I suppose their nest sites are much safer from predators, and that helps explain it. But enough about wasps for now! Just remember, only in natural areas can you fully study natural phenomena. You need a guide, for the place will seem empty to an uninformed tourist.

You need a guide to unlock the mysteries, or even to know there are mysteries.

Frank Blair’s small mammal fences.

Some studies just need some land for planting. They may or may not be dependent on the surrounding wildness.

The tractor shed where I first studied wasps.

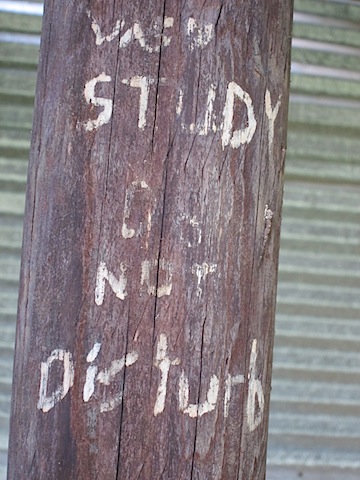

My sign.

Polistes exclamans, queen and male, her son. Wonder where the workers are. It looks like at least 3 besides this male have hatched out of this nest.

Another nest, with a queen on top, waving her legs in threat at me, two workers in the middle (always female), and a male bottom left.

A leaf-wing butterfly, genus Anaea, what the baits are for.

Hackberry butterflies, Asterocampa, opportunistically also studied by an undergraduate.